The “Rare but Serious” Side Effect That Could Have Killed my Sister

Tips and Tricks for Improving Multiple Sclerosis

[Author’s Note: This story first appeared on Multiple Sclerosis News Today.]

It started out with mosquito bites, three of them, high up on my sister’s thigh. At the time, we didn’t think much about it. It was a weird spot but in New Hampshire, late-season mosquitoes are persistent little beggars. Margaret just scratched and bought a tube of AfterBite at the pharmacy, where she’d gone to pick up antacids. The next day, it was cream for a yeast infection. A day or two after, she had a sore throat, then a rash, then a fever spiking so fast that in the amount of time it took to shake down the thermometer from one reading to the next, her temperature rose half a degree.

By then, we knew the red spots weren’t mosquito bites, they were hives. It would be another three days before we had an official diagnosis that tied together all of her symptoms: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), a skin and mucous-membrane disorder with a mortality rate of 25%.

By then, we knew the red spots weren’t mosquito bites, they were hives. It would be another three days before we had an official diagnosis that tied together all of her symptoms: Stevens-Johnson Syndrome (SJS), a skin and mucous-membrane disorder with a mortality rate of 25%.

Think of that line from the drug commercials that usually follows the rapid-fire listing of side effects: Call your doctor immediately if [insert phrase here], as this may be a sign of a rare but serious side effect. For drugs as varied as carbamazepine, Naprosyn, and even ibuprofen and acetaminophen, the FDA doesn’t mince words: that reaction is characterized as not just serious but sometimes fatal. And its name is SJS.

Stevens-Johnson syndrome is not a drug allergy. It is a chemical reaction that takes place in the cells of your skin and mucous membranes such as your mouth, ears, nose, eyes, lungs, G.I. tract, and genitals. Basically, exposure to some agent causes the immune system to go haywire and began releasing signaling chemicals that trigger cell death. A red or purple rash springs up that forms blisters that burst and then peel. This is the danger with SJS—as the spots grow together, large swaths of skin can be stripped away, leaving the sufferer vulnerable to infection. SJS requires immediate hospitalization, frequently in the ICU or burn unit.

Treating SJS

In the case of my sister Margaret, who was visiting me, the expertise at my small-town hospital was just good enough to give her diagnosis. Fortunately, we live an hour away from Boston. We were able to get her transferred to Brigham & Women’s Hospital, a facility listed on the US News & World Report Honor Roll of top US hospitals.

No sooner had she been admitted then, like somebody in an Edward Jones commercial, she had people—a dermatology team, an ophthalmology team, a gynecology team, and a general medicine team. They put tissue grafts in her eyes to protect her vision—the eyelids are lined by mucous membranes and affected by SJS, as well. They can form blisters and during the healing process grow onto the cornea, leading to vision damage or even blindness. In Margaret’s case, the grafts prevented this issue.

According to the doctors, she had a mild case. Mild. A month in the hospital, agonizing pain, unable to see because of the tissue grafts in her eyes. Mild.

For Margaret, the culprit appeared to be carbamazepine, a drug her neurologist had recently prescribed to her for pain caused by her trigeminal neuralgia. For years, she has practiced self hypnosis for pain control, resorting to the drugs only in her most agonizing moments. Now, that has been taken from her. She can’t ever take any drug from that family again.

Know the symptoms

SJS is a very rare disorder¾you’re more likely to be struck by lightning than contract SJS. For carbamazepine users, however, SJS is far more common—FDA labeling estimates that as many as six of every 10,000 new users will experience SJS. And carbamazepine is the go-to drug for treating trigeminal neuralgia.

None of this is to suggest that you quit or avoid taking carbamazepine. Just educate yourself. Speed of response has an enormous effect on prognosis. Talk to your doctor and make sure you know the symptoms. Be aware that the disorder can occur at any time, whether on your first dose of a new medication or your 301st. And most of all, educate those around you so that if anybody begins to contract SJS, they get to the hospital as quickly as possible.

Over a year has passed since Margaret’s illness. While not entirely recovered, she is past the worst of it and it appears that she won’t have significant lasting effects. One thing is certain, though¾we won’t ever look at a simple mosquito bite in the same way again.

Disclaimer

Hack My MS provides news and information only. It is an account of my own experiences and some techniques that have worked for me. It should not be construed as medical advice, nor is there any guarantee that any of these techniques will work for you. Always check with a medical professional before starting any exercise program, treatment, or medication. Do not discontinue any exercise program/medication/treatment or delay seeing a doctor as a result of anything you read on this site.

Neuro Muscular Electrical Stimulation: A Practical Guide, Lucinda L. Baker

Neuro Muscular Electrical Stimulation: A Practical Guide, Lucinda L. Baker Manual Of Structural Kinesiology, RT Floyd

Manual Of Structural Kinesiology, RT Floyd Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation, Donald A. Neumann

Kinesiology of the Musculoskeletal System: Foundations for Rehabilitation, Donald A. Neumann The Extremities: Muscles and Motor Points, John H. Warfel

The Extremities: Muscles and Motor Points, John H. Warfel Application of Muscle/Nerve Stimulation in Health and Disease, Gerta Vrbová

Application of Muscle/Nerve Stimulation in Health and Disease, Gerta Vrbová Minding My Mitochondria, Terry L. Wahls

Minding My Mitochondria, Terry L. Wahls

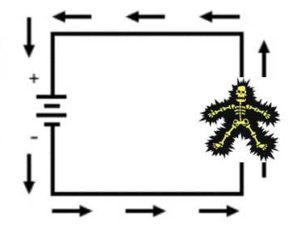

Electrical circuits only work when they run in loops – current starts in the battery, runs around the circuit and returns to the battery. With NMES, the current makes a little side detour through part of your body. Specifically, the current goes through your skin into your nerve, through the muscle, out of the muscle, back to the skin and up the wire back into the box. Yep, we’re basically ignoring all of those stickers on your blow dryer cord that say don’t drop it into your bathwater because you’ll run current through your body. In this case, running current through your body is the point.

Electrical circuits only work when they run in loops – current starts in the battery, runs around the circuit and returns to the battery. With NMES, the current makes a little side detour through part of your body. Specifically, the current goes through your skin into your nerve, through the muscle, out of the muscle, back to the skin and up the wire back into the box. Yep, we’re basically ignoring all of those stickers on your blow dryer cord that say don’t drop it into your bathwater because you’ll run current through your body. In this case, running current through your body is the point.